The story of Humboldt County’s cannabis economy is not a single narrative but a collection of lived experiences shaped by land, labor, community, survival, and change. For decades, small family farms, intergenerational growers, and informal networks built what many came to know as the backbone of Northern California’s underground economy. Legalization promised safety, stability, and opportunity, yet the transition also brought unexpected challenges: regulatory barriers, corporate expansion, displacement of small farmers, and shifting cultural meaning.

“The Green Rush” oral history series, hosted by Little Lost Forest, documents these personal histories so they are not lost to policy debates or economic statistics. Through conversations with growers, workers, and community members, this project explores how legalization transformed livelihoods, local identity, and the broader economic landscape of Humboldt County.

This interview offers one perspective from someone who grew up in a multigenerational cannabis family, witnessing both the era of small-farm prosperity and the dramatic restructuring that followed legalization. Their reflections highlight the resilience of Humboldt communities while also raising difficult questions about who benefits—and who is left behind—when an informal economy becomes regulated and industrialized.

As you read, consider this interview not only as a personal story, but as part of a larger collective archive documenting the rise, transformation, and ongoing evolution of the region’s cannabis culture.

Natascha: Hello. And thank you for participating in the Little Lost Forest interview focused on Humboldt County’s economic growth and decline surrounding the legalization of cannabis. My name is Natascha, and today I’m sitting with CannaClaus. CannaClaus, where are you calling from?

CannaClaus: Arcata, California.

Natascha: How are you doing today?

CannaClaus: I’m doing great, relaxing day.

Natascha: Sweet. How would you define the cannabis culture prior to legalization?

CannaClaus: Prior to legalization was the black market, and it was small families and small farms. There was my great-grandfather and grandfather grew hemp for World War II and Vietnam or something like that. Then there was a huge struggle and the 70s and 80s between northern and southern Humble and Mendocino and the Emerald triangle, there’s a lot of fights and a lot of back-alley deals, and a lot of people died and things happened. And then we got into the 80s and 90s, and it was more like what I was just explaining at the beginning. Small farms, small families. It became the grandmas and grandpas. And then pretty soon, the industry was legalized, and the big guys came in.

Natascha: What would you say your first job in the cannabis industry was?

CannaClaus: My first job. Let me see. I started making clones for my family farm when I was about 11.

Natascha: Wow, that’s super young. What was the economy like during that time?

CannaClaus: Oh, for Humboldt, it was booming. Fisheries were booming; the logging was booming. And then marijuana was our third big– How do you say just big profession out here, that Humboldt County. Everywhere. Everybody was killing it.

Natascha: How would you describe community relationships and even mutual support during these early years?

CannaClaus: Oh, during the early years, you had, it wasn’t black ops, but it was, God, I forget what they camped. They used to have camp that rolled around in black helicopters and went around with the police forces and tried to get everybody and catch everybody and get these families, even though they label us as drug dealers or bad people. But it was really just families trying to make a living and get a little extra on the side to have a nice vacation or something. It was really nice because the community understood that, like when the cops in camp would come to town, they would go meet somewhere, like in a big parking lot or a restaurant, and all the farmers and everybody everywhere would start getting the phone calls. Hey, they’re on this mountain on this side. They’re coming up these roads. And so we would all get ready for them. And it wasn’t get ready for them, like get your guns or nothing. It was get ready for them and lock your gates, lock down. Get, you know, kids out of there if there’s kids there and so forth, and get ready for these helicopters, because they used to come into our greenhouses and fly as close as they could to them to bust the top of the greenhouse off. So, if they can visualize and see inside there and see actual marijuana, even if you want or not. You had a farm in the greenhouse. They’re going to try it. If they blew that top off and see marijuana, they can come down and rope down into your property with their big AKs. They’re mean people. So.

Natascha: Why do you think people kept growing after that?

CannaClaus: I know that I kept growing after that just because the money was good. I had more time to spend with my family. We made good money. We were able to donate and share in the community. My family, along with many other families, always donated our extras to people that couldn’t spend the money for it or that needed it. We also

would set up fundraisers for the veterans, and it was called Weed for Veterans. And we would go around and make big meals and hand them out to the homeless in different places and the community. I mean, with all the money we’re getting in and all the taxes and everything. I mean, the city was doing really well and doing really good for itself and starting to clean itself up because we all know in the 80s and 90s around here that it was pretty trashed. And then the city started cleaning up.

Natascha: What do you mean, literally trashed?

CannaClaus: Or pretty much. I mean, all the downtowns, all the parks. I mean, we just started getting new parks like this last ten years.

CannaClaus: The homeless rate went skyrocketed when I was a kid. It was just you went; you walked from the mall up to like the bay or whatever. The back parts over there, you’d always see like 2 or 3 little homeless camps. And now with the fentanyl and heroin and meth and all that stuff, those homeless camps have grown to hundreds, hundreds, and hundreds. The community lately has gotten them to where they’re compacted in certain areas. They move in and clean up after them and then move them back out. A lot of community members are finding ways to come together to help them and get them off the streets in different ways and stuff. The drugs made it so bad, and everybody always blames pot or pot’s a gateway drug or blah blah. No, that’s not true at all. I don’t believe it. I believe alcohol is more of a gateway drug than anything, but I think I got off topic there. Sorry about that.

Natascha: No. It’s good. I want to dig into this. Just one more question. Do you feel like the cannabis industry brought in a lot of traveling folks or homeless people?

CannaClaus: I definitely think it brought in a lot of traveling people, because every summer we call them trim-igrants, and they would come in usually around August, September, and you would just see them hanging out at Murphy’s or Safeways or Winco’s or, grow stores or different places like that, finding work because they can come here and get a visa, like a student visa or like a visiting visa and trim for three months from September to November, or mattering how big the farm was. And they would make anywhere from like 10 to 20 grand trimming because they can make around 200 to 300 a pound. And then it went down to last, or ten years ago; it went down to 100 a pound. And then five years ago, it went down to 60 a pound. And then the machine trimmers started coming out. Then they would just pay them, you know, 15 or 20 bucks an hour to run the machine trim, and then they would give them 40 bucks a pound to clean it up. And so, then those people are slowing down and not coming out here as much. I believe the homeless rate around here is due to these, I forget what it’s called, it’s not like asylum cities or whatever, but they we have buses that literally pick

up homeless people from different cities and places of the state and just drop them off here.

Natascha: Right. Would you say that trim-igrants were bringing money into the economy in Humboldt?

CannaClaus: No, no, they took it out.

Natascha: Okay.

CannaClaus: Because they would make their 15-20 grand and go back home to their families. And I know a lot of them that would make around 20 grand or whatever, and 20 American US dollars. They would go back home and go to school or learn a trade or do whatever, and just live the whole year off of that, and then come back and do it again.

Natascha: How big was your family farm?

CannaClaus: We had three farms, I think, at the most. My farm was an acre and a half. My two sisters, I have three sisters: two of them grew. The other one had a two-acre farm. And the oldest sister, she had a 40-acre farm.

Natascha: Did any of them stay in business?

CannaClaus: My sister [Heather] was the last one to go out of business. And this was this last year. They came out to the property. Our permits weren’t all aligned, and we were still going through paperwork and getting everything ready with the state, the city, the county, and da da da. And every loophole that they make you jump through and every paper they have, you triplicate and sign and bring back and take here and spend this. I mean, literally just trying to get legal or legalized was costing around 100 to $150,000. And these farmers are now, with outdoor farmers anyways, are now only making, 200 to 400 max on a pound. And when you put in your time, energy, food, water, hourly wage, you’re making like 20 bucks an hour. It’s just not worth it anymore. Everybody thinks marijuana is like it grows on trees, like money grows on trees, and that’s marijuana. That was when we were getting indoor for 3000. That’s when we were getting outdoor for 1500, you know. Now indoors 1000 and outdoors 200 to 400. And

depths are like 500 to 600 max. You know, you can’t make a living wage off of that anymore. You might as well just go get a regular job.

Natascha: What was the furthest license that you got on your farm?

CannaClaus: Mine was medical. I’ve always done medical. I never got permitted. I just always did my 99 plants. And I would donate half of my crop to different people that needed it. Every ounce I sold, every pound I sold; I would donate an ounce or donate a pound. And everything I got to people was people that had medical cannabis cards and actually needed it. I never was for the legalization of it, just for anybody over 18 to smoke marijuana. I don’t think it’s for everybody. I believe marijuana can really make a person way dumber and just do idiotic things and become slow and not learn trades or learn skills and just become a slug. But when it’s medically grown and it’s for medical reasons for people that actually need it. They use it in the right way. I believe it’s a miracle drug. And I love it. Love it to death.

Natascha: Well, that’s great that you were able to donate to people because that would help boost economic growth. Let’s say there’s somebody that is not working in their career path or maybe somebody struggling to pay rent. They could utilize the cannabis to also help them financially into a better financial situation. I would assume.

CannaClaus: That’s why we helped a lot of the vets because it’s, you know, it’s still a class one. All these years, every summer we get together, and we get all the farmers together and do a bit of weed for vets. They come around and we give them their dabs and their flowers and things and utensils to work with it and different meditations. And just like every booth has something different. If everything was free, everything was free. If you’re a vet, everything was free. So that was super cool. And I mean, if you can’t give back and you can’t get good karma in this life, then it’s not worth doing.

Natascha: Yeah. Super green work. Uh, how did you protect your farm?

CannaClaus: Back in the early days in the 90s and stuff. I mean, we protect it with our dogs and our guns. It’s not, you know, the ideal suit for having a family around it and stuff. But my dad was in his early days a very hardcore mountain man. And he felt like what came from the earth is what we’re allowed to. And then we can do what we need to do– what we want with it. And the actual human laws only follow the ones that do

right and do good. And the ones that don’t make any sense or that are about government, taking your money, or blah, blah, blah, don’t follow those ones. Stay true to your mountain, your mountain heart, and everything. And then once we got older and we didn’t have to have the guns anymore and, well, besides for bears and mountain lions and stuff, and the dogs became more of family pets, other than the protections of the farm, even though they still were out there for rattlesnakes, mountain lions, bears, different stuff like that. It got a lot more chill. And then in the 2010s, we started getting a lot of people coming from like Hurricane Katrina and different people coming up from Oakland and Richmond and stuff like that, and coming up and lobbying everybody.

CannaClaus: And so then we had to bring back out the protection and come back as a community and make phone calls. And then we had social media by that time to be able to share people’s pictures or videos or different stuff with these thieves coming through town, or fake money, or fake this, or fake cops or whatever it is. Then the legalization or recreation, I mean, it dropped the price tremendously. Nobody really cares about robbing you anymore because it’s not worth it. I just seen a post the other day. A cop pulled me over and got 60 lbs of marijuana, and they’re like, we’re keeping our Trinity County safe. And every single comment on there along with mine is, oh my God, you got 60lbs. Like, oh, it’s like six grand worth of money. And you just hurt a family that was struggling to make ends meet this year. And you guys think you’re keeping the community safe from these pot dwellers. You know, everybody’s just laughing at them. It’s just dumb. Like, get this meth and get this fentanyl off these streets. And that’s how I lost my little sister this year, a couple months ago was from fentanyl. I just wish the cops paid more attention to that and just still paying attention to pot, like, come on, dude, get out of here, guys.

Natascha: Yeah. I’m so sorry to hear that.

CannaClaus: Yeah. It sucks.

Natascha: How did you sell your product?

CannaClaus: Before I got medically licensed, I did black market or through family and friends. And, I mean, I started early. I used to roll joints in seventh and eighth grade, and I would sell them, uh, two for 5 or 1 for three. Okay. And then when I got to high school, we got our first house, a little tiny house my dad got. And we lived in trailers and

projects and stuff before that. We got our first house, and he needed help with paying the mortgage and different things. And so, I started selling bud and to friends and people in school. And then I got really entwined in the marijuana community because of my family name and everything. I started growing my sophomore year outdoors, and then I started growing indoors after I left high school and went to college. I started doing my indoor scene, and everything was still really going black market. Then I became medically legal when I was twenty-eight, I believe, which was 13 years ago. And then I because from 2020-28 I worked for an oil change place, and just went straight and narrow for a while, just to see the other side of life, and just not be around

CannaClaus: The price was dropping then, too, but not like it is now. And I just wanted to do something different. Um, then I went back at 28, and at 30, um, I had a medical delivery service in Eureka in Humboldt County. And then I started another one in New Jersey. And to get product out there for my medical patients, which, again, I was a straight medical, I had to drive it out there, and I had a friend or a partner that would drive it out there for me, but he ended up breaking down, in Sacramento. And so, I went and got a rental car and put it in the back and tried to make it myself and got pulled over in Ohio, about four hours away from where I was, and ended up doing almost two years in the Ohio prison system. So.

Natascha: Is there anything else you would like to add to that? Maybe, the way that they treat cannabis growers and the jail system or the way that the judge

CannaClaus: They acted like we were the biggest drug dealers. I actually had a lot of seniority or like, higher up, mentality in that prison because I only had 100lbs on me when I got caught. And 100lbs out here is like, like a medium to average guy out there, 100lbs they acted like I was some kind of mafia boss. They pulled me into a back room and tried to get me to, like, say some names, and we’ll let you go, or we’ll give you a lighter sentence. And I was like, what do you mean? I was like, I grew it. It’s my company. I packaged it, and I drove it. So, if you want a name, here’s the name CannaClaus, motherfucker. And then when I got to the police station, they had the news station out there, and they were laughing at me and pointing at me in the car. When I got to prison, the actual inmates treated me very well. Actually, a lot of inmates and a lot of society inside of prison is very respectable. You respect others, you respect your place, you respect your space, their space. And everybody has their hierarchy.

Then there’s the CEO, the correctional officers, which are just the biggest dicks I’ve ever met in life. That anybody or anywhere they have a seniority or like a senior complex, but like a bully, like they were either bullied in school, or they bullied people in school, and they get to do it again. They would make fun of me and call me a California fag.

CannaClaus: Why can’t- and I had another correctional officer ask me, well, why can’t you guys just make pills? Just make pills like all the other doctors do? And I was like, we do make pills. I was like, I got pulled over with pills. I was like, I had CBD pills, and I had THC pills, and I had a THC, CBD, hybrid pill. And I was like- and they were for specific patients. And everybody is different. Every patient is different. You can smoke, one patient can smoke flower all day, and just have a great life. Another patient smokes flower and has an allergic reaction. One patient like me, I- I cannot eat edibles. I can smoke dabs and marijuana all day. Be completely normal. Fine. You know, do everything I can in a normal day. But if I eat an edible, I am shaking, I am paranoid, I am sitting on the couch. I am trying to figure out how to get this to stop. So, everybody’s body is different. And I was trying to explain that to him. And then, you know, just says a bunch of messed-up racist and sexist things to me because I’m a California boy, I must be a surfer or stuff like that. You don’t even know what you’re talking about.

Natascha: Right.

CannaClaus: When I got pulled over, and they were making fun of me and talking to me about being a drug dealer, I was like, that’s funny, because in your state, marijuana is illegal, but you can fuck your dog. I was like, you guys, bestiality in Ohio right now is legal, and marijuana is illegal. And I go, so you guys are completely backwards over here, dude. And they would say a bunch of, you know, mean stuff to me, drugs, blah, blah, blah, blah. And I go, go fuck your German Shepherd motherfucker. We talked a lot of shit back and forth, and I didn’t get along with the correction officers, but the inmates treated me really nicely and respectfully. And a lot of movies, a lot of working out, and a lot of books. That’s about it on that one.

Natascha: Yeah. When you reflect on your upbringing, was the lifestyle desirable?

CannaClaus: When I was a kid, to make a long story short, my parents divorced when I was two, and the courts back then always gave the kids to the mother. My mother was a heroin addict for 28 years, and so we lived a really bad childhood for about 4 or 5 years. I ended up going to the hospital for malnutrition and passing away for a little bit, but they brought me back, and I was bedridden for a year.

Natascha: Oh.

CannaClaus: My sisters and my grandma raised me. And then my dad finally got us back from the court system, and then he raised us all the way until we were adults. And then my mom came back into the picture once we were- I’m the youngest. So, once I turned 18, she came back, and she cleaned up everything. She stopped drugs, she stopped drinking. She stopped smoking cigarettes. And she’s been the best grandma and just an amazing person. These last years. But after that childhood with the badness, and us going with my father, and my father being a pot grower. We spent a lot of time in the woods, fishing, hunting, hiking, cracking, and doing all that fun stuff these Humboldt kids do. It was very nice at that point, and I did love it a lot, but we were wary of out-of-towners coming in or people trying to rob the farm or bears, mountain lions, and snakes, and so forth. You know what you have to worry about out in the mountains. But other than that, it wasn’t. It was a good childhood.

Natascha: Was it worth it in your adult years, going to jail over cannabis?

CannaClaus: No, because my son was nine months old when I went. When I got back out, he was two years old , and I missed his first steps. I missed a lot of his first- a lot of things. [Voice strains] When I was in prison, I used to watch the sunset every night and know that my son was almost 2000 miles away, and there’s nothing I can do about it. Constantly looking at fences, barbed wire, razor wire, and guards with guns. Even though prisoners were respectful of each other, they were still, you know, people on drugs or gangs or stuff that, those fights or different kinds of crazy things that happened. I would definitely change it. And that’s what I did when I got back out. When I got out of prison, I just got a normal job and didn’t care if I made good money or not. And if we were poor or rich or not. As long as I had time with my son every day. There was never a chance of him being taken from me again. I’ll live that life over odds or money or anything. So that’s when I made that choice.

Natascha: Beautiful. What was the hope in legalization? Did you see hope in the community?

CannaClaus: I did. When we finally got medical, it was awesome. It was so cool. We could finally come out of the woodworks and out of the shadows, and we all did anyway, but we couldn’t do it in front of cops. And then it was like all of a sudden, like, we can actually be stoned and not worry or be paranoid of these cops coming in and robbing us, just stealing from us. And this still happens, especially with Camp and Officer *******. That guy robbed me quite a few times. And there were other crooked cops, but that was the one that messed with me. And a lot of people around here ended up passing away on 36. There was a landslide that ended up killing them last year, I believe. And I’m sorry for the family and everything, but that guy was a piece of crap, and he would rob a lot of us. Take our money, take our pot, and take our hash. No write-ups, no tickets, no nothing. See you later. You know. And I’m sorry. What was the question again on that one?

Natascha: We were talking about the hopes of legalization, that things would continue to thrive.

CannaClaus: When it became medically legal, it was awesome. And we were all super stoked. And then we thought the legalization of recreational, which I didn’t vote for, but the thought of everybody else in the talk around town and through our small knit groups and everything, was that we can finally be free of the police and free of the FBI and different places coming in and robbing us and taking us and taking our kids away from us, or taking our properties away from us or our, um, annual income for the year to feed us or pay our bills or whatever. And then what it did was when recreational became legal. These bigger companies came in, and they still shut down our smaller farms with all the processes, paperwork, and permits, and you gotta pay taxes on every single acre. You got to pay taxes on every single square foot. You’ve got to pay taxes on how many plants you grow, even though they don’t understand that plants, just like any other crop, you’re going to have pests, you’re going to have molds, you’re going to have bears, deer, all sorts of things that happen. And no matter what, you still got to pay the taxes on that square foot. And for that plant. And they made it impossible for us small guys to go through.

CannaClaus: So, they shut down about 90% of our small farms out here. And all the big guys came through, and they’re buying these big chunks of the mountain. And another big one, I forget what it’s called- it’s a greenhouse world, the greenhouse

something. And it was a bunch of old police officers that got together, and they were the ones that drove a bunch of us out, got together and bought a big parcels of these mountains, and now they’re doing all these legal grows that provide to all these little shops and everything everywhere. But most of it goes down to LA and San Francisco, and they just completely- we thought it was going to be a good thing, but most people didn’t. I didn’t, but most people did. They ended up biting us in the ass to where all these families and home grows and family-oriented and family this and grandma and grandpa and small farms, they’re pretty much all gone. You rarely see any of them out here anymore. And it’s just these big farmer grows now, and it’s just going to get worse. I think I’ve heard Philip Morris was coming in and buying some of the mountains up here.

Natascha: Where do you think these small farms went? Where did those families go? What happened to them?

CannaClaus: I knew about between 50 and 60 different families and farms here, and most of them went to Oregon to try their hand up there because it was cheaper land, still beautiful land. A lot more wet. So, you have a little bit of a different season up there due to mold and snow. A lot of them went up there with the last bit of money they had; some went to Washington. Same thing. Then others sold their farms at a high price or sold their stuff at a high price. But, you know, back in the day and got out of it real fast and started up little shops or things around the town, either a Mexican restaurant or a nail salon or a barber and they just started their own little businesses or food trucks. God, we have like 30 food trucks now. It’s ridiculous. They tried their hand at something different. What I did was I had my little indoor, my little greenhouse out in the backyard for my own little personal and my own family personal. But other than that, I went and got a job with a big lumber company. That’s one of our big things out here is lumber and fish. It used to be lumber fish, and pot, but now it’s just- now the fishing is dying too. Pacific seafood or whatever, shut down, and lumber is basically the only thing we have left out here. And it’s getting hard.

Natascha: Would you say there’s more or less crime now than before legalization?

CannaClaus: There was more crime prior, for pot and people coming up from Richmond and Oakland and stuff, and robbing us. But there’s more crime now due to fentanyl and hard drugs that are up here, eating all of our kids. Crime in all genres, there’s more crime now. But if you’re looking at crime for just marijuana, crime now for marijuana is down, and crime back then was up.

Natascha: How would you say legalization has affected labor, jobs, wages, and housing in this area?

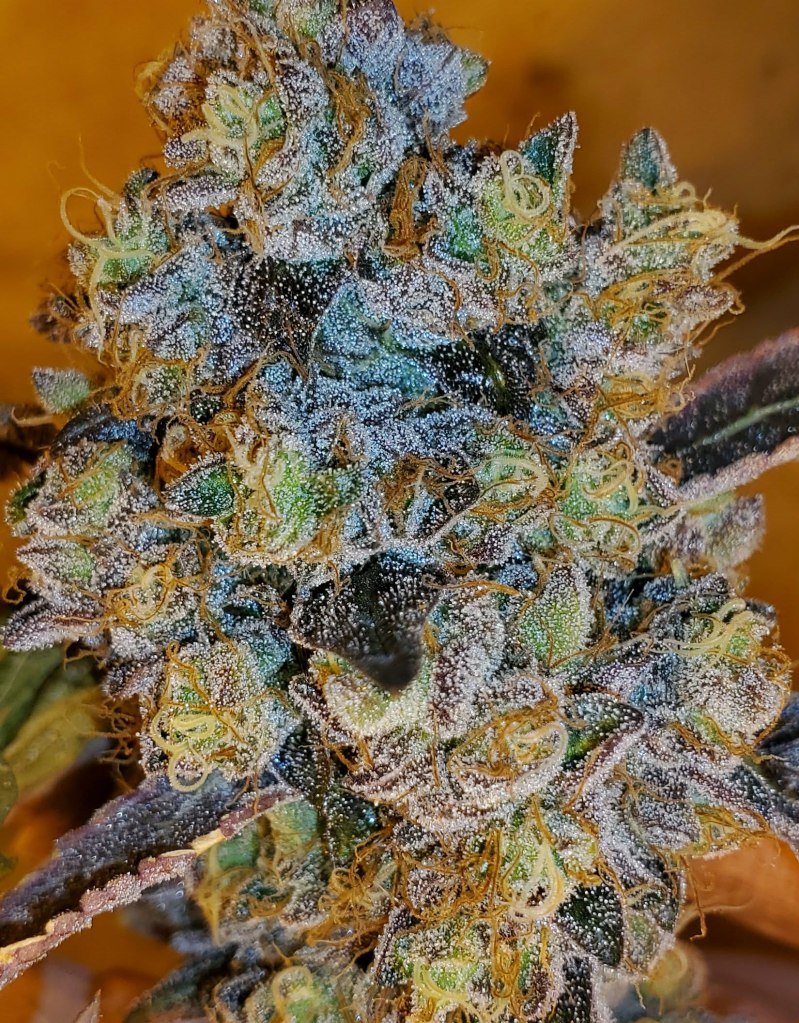

CannaClaus: Housing went way up. Jobs, because I think when COVID hit and everything, we were all able to get jobs and go back to work and do stuff. When I was younger, I used to have to hit, you know, 20 different places with a resume and an application to get one job. And now there are 30 to 40 places hitting you up to get a job. So I think there’s plenty of more jobs out there. I don’t know if it’s just this younger generation doesn’t want to work, or they’re going to school and buying into crypto or whatever the hell they’re doing. They’re not having to work as much. And so there’s a lot more jobs, but I just believe it’s for different reasons than the legalization. Legalization and the pot market trimming jobs went down, trim-igrants coming in went down, Money coming into the county went down, because now all the people from the East Coast that used to come out here and buy our pot because we have the best pot growing in the triangle, and then bring it back out to the rest of the country. Now they have all these farms in these middle states, and it’s all this really fast-growing weed. It’s called autoflower. And they made a hybrid of a flower that can; it grows to a certain height, and then it just automatically flowers no matter what season it is, no matter how much sun it gets, how much light it gets; it grows to a certain height and then flowers. They have these massive- where it used to be cornfields- it’s just pot fields. It’s the pot that looks really nice and really pretty.

CannaClaus: But they spray them with pesticides. They have tons of chemicals in them. And now these East Coast people, they don’t care that the pot’s not Humboldt, grown. And it’s this beautiful, amazing pot. The more care, distance, time, money, and it still looks and smells good. I don’t give a fuck if it has chemicals or bad things in it for my clients, I don’t care. I’m here to make money. So, all these East Coast people used to bring us money, but that’s gone. All the trim-igrants coming in used to take our money, but they helped us thrive. They helped us trim our product. So it wasn’t horrible to let that money go. They were helpful. The trimming jobs for just your sisters and brothers or cousins and nephews or whatever, that’s gone. There’s no more trimming jobs. All the places that were doing really good and the farms were expanding. Once the location hit, boom, they hit us with all these taxes and these permits and these paperworks, and then they can legally know, because all these farms tried; they really tried, and they put up all these fences and made it so hard that we couldn’t. And then they knew where we were. So, we just put ourselves on the map, and they came in and started busting everybody that way. ‘Like, oh, we see that you tried and failed. So now I’m going to take your farm. Now we know where you’re at. Now we know where to get you.’ The realization medical was good, but recreational just destroyed the community.

Natascha: Did you witness economic stress, displacement, or loss within the community?

CannaClaus: Yeah. Yeah, a lot of people, like I said, a lot of people moved to Oregon and Washington. A lot of people left. They were fleeing where? Humboldt County and California, people usually fleeing to.

Natascha: Mhm.

CannaClaus: Nowadays, I see people fleeing from. Rents too high, mortgages too high, rates are too high, foods too high, gas too high, fires. There’s no more money in pot anymore. So, everybody’s just like there’s no reason to live here anymore. Why can’t I just go to Texas or go to these other states and buy a mansion for a hundred grand? When out here, a hundred grand gets you a one-bedroom shack. So, it ruined it.

Natascha: What do you think the long-term effects of cannabis legalization are going to be on Humboldt County?

CannaClaus: Oh, it’s just going to be sold at Walmart, Target, and everywhere else. You pick up alcohol and cigarettes behind the counter. You’re going to have your pre rolled swishers, your pre-rolled joints and, all these dispensaries around here, they’re

going to pretty soon they’re going to be gone. It’s going to be in the classification of it- goes from class one to class three. And they can start studying it inside of the colleges, and it becomes recreational legal around the country. Walmart and Amazon, and all that. It’s going to take over, and there’s going to be big farms and big farmers, but

it’s going to be from big pharma, like it’s going to be the one percenters that own it. Then we work it for them, and then they sell it through Walmart and Amazon for that stuff. It’s going to be delivered right to the house. Most of it’s going to be crap. I believe it’s going to be like wine; you got your $5 bottles of wine you can get at Costco or WinCo, but then you have your thousand-dollar bottles of wine that are amazing and tasteful and age and so forth. So, I believe there will still be small farmers, like real petite small farmers, like you would have at a farmer’s market. But other than that, there’s not going to be anything like we do right now. It’s all going to be gone.

Natascha: What hopes do you have for the future of Humboldt County?

CannaClaus: Well, if we can become sustainable in the logging community and keep doing what we’re doing, like Sierra Pacific and the other guys, North Fork and stuff that they’re doing. Every time they go and cut down a bunch of trees, they’re replanting and reforming and going forth. And so that’s been awesome. And now that we’ve got these dams out of the Klamath and so forth in different places. The fish is starting to come

back. So, I have hopes, hope the fishery markets come back, and then we can provide and supply our county off of that, and the logging, and we won’t have to worry about pot anymore. Everybody will have their small homebrews and stuff like that. But other than that, there is no money anymore. There’s no making a company out of it anymore. It’s going to be Amazon and Walmart and so forth that will have that corner of the market. Fishing and logging stay sustainable, and as a county, we can make it through that. But other than that, there’s nothing else we have up here. Maybe solar, maybe some kind of hydro from ocean waves, or something like that. But I don’t see anything else coming from up here.

Natascha: Can you describe the local cannabis culture today?

CannaClaus: It’s like where you used to go out to the plaza and give nugs to the homeless guys around there and stuff, and be really proud of it and be really happy that they get this really nice medical tasty, you know, strain. And now you go out there to give it to them, and they give you some back. And there’s so much of it everywhere. And everybody has it that it’s not a present anymore. It’s not special anymore. It used to be like you go and get a coffee ,and you give a nice tip. Now you have to give a bud to somebody, and they just say, nah I don’t need it or I don’t want it. It’s not special

anymore. Cannabis up here has changed to just basically taking your medicine at night. Everybody takes their gummies at night, or everybody smokes a joint on a road trip or something, you know? But it’s nothing. It’s not like it was. It’s not nostalgic anymore. And I don’t know, maybe it’s because I’m getting older, but that’s how I see it.

Natascha: No, I think that’s very true. I can think of instances when I was a trimmer, and I gave people a jar of weed, and they’d be so excited. You’re right, now everyone’s kind of got their own boutique stuff from the dispensaries that they’re paying $50 for an eighth or whatever.

CannaClaus: Yeah. It’s ridiculous. Mine’s always been organic, so it’s always just fucking tasty and beautiful and white ash and just the best of the best. But then, you know, if I’m out or can’t get any, then they go to dispensaries and get a, you know, an ounce of indoor for 60 bucks or 80 bucks, but it’s just crap, you know? Like, it’s pretty, but it’s old or stinks, or it’s chemical-bound or so forth.

CannaClaus: It’s crazy.

Natascha: My last question for you is: Can you detail how the cannabis farms prior to legalization helped the Humboldt community?

CannaClaus: To the legalization of recreational.

Natascha: Yes.

CannaClaus: How did they help the community?

Natascha: Yeah, the economy in Humboldt.

CannaClaus: Well, I mean, that’s how they brought in so much money because we’re still black market and medical. It went from 4000 to 3000 to 2000 a pound, but it was still 2,000lb, still good money. We were still bringing in a lot of money into this economy up there. The roads are getting fixed. The schools are getting fixed. More shops were opening up, where you have your pot farm and husband or your pot-farming family. You had a cousin, a nephew, a niece, a wife, or somebody who was starting a business in town. And so, there were a lot of businesses started off of the pot community and the

medical and black market. But once it became recreationally legal and you had to get these permits and licenses, everybody spent their money trying to do that, or trying to get away from it, or trying to hide from it, or trying to go with it. And it was pretty much a loss. There’s abandoned farms, there’s thieves that came through and stole the good and left those people that have molded, hundreds or thousands of pounds of mold-weed just sitting in a basement somewhere because it couldn’t sell. It’s optimal utilization. The economy definitely took a huge hit, and it happened right when COVID hit and all that stuff too. This whole community has been struggling so hard. I’m not for any of these presidents, liking neither Trump nor Biden. And yet they’re all crap. All rich white men that are pedophiles and pieces of shit. I’m not for any of them. I’m not a Democrat, a Republican, a leftist, or a rightist. I’m for doing what’s right, being part of the community, and living life to be as happy as you can before your last day comes. And with COVID, the politics, and the realization of this community, the prices of everything are going up. We are struggling so badly out there, it’s ridiculous.

Natascha: Yeah, I hear you on that. Well, thank you so much for sharing your story and your time. Your experiences are an important part of Humboldt County’s living history.

The story shared here is one voice among many that together form the living history of Humboldt County’s cannabis era. Behind policy changes and market statistics are families, workers, and communities whose livelihoods, identities, and landscapes were shaped by the rise—and transformation—of this industry. Listening to these experiences reminds us that economic shifts are never abstract; they are deeply personal, carried in memories of land worked, risks taken, communities built, and futures reimagined.

Little Lost Forest continues to collect these stories to ensure that the cultural, social, and economic legacy of the Green Rush is preserved in the words of those who lived it. If you or someone you know would like to share your experience, we invite you to contribute—because the history of Humboldt County is still being written, and every story helps illuminate the full picture.

Photo Disclaimer: The photographs accompanying this article are presented for journalistic, historical, and educational documentation purposes only. They are intended to reflect the lived experiences, cultural history, and economic realities discussed within the oral-history project “The Green Rush: NorCal — The Rise and Fall of Humboldt County’s Cannabis Economy.”

Little Lost Forest does not promote illegal activity or the sale, distribution, or misuse of cannabis. All content is shared to preserve regional history, community narratives, and research-based storytelling. Viewers are encouraged to follow all local, state, and federal laws regarding cannabis in their area.

Participation in this project is voluntary, and identifying details may be altered or anonymized when requested to protect the privacy and safety of contributors.